Children Fed Radioactive Oatmeal?! The Shocking Lab Test

Picture young boys sitting down to breakfast in a Massachusetts institution, unaware that their morning oatmeal harbors an invisible danger. You've probably heard stories of unethical medical experiments, but the Fernald School case hits particularly close to home. When scientists fed radioactive tracers to developmentally disabled children under the guise of a "science club," they crossed a line that would forever change research ethics. What you're about to discover will make you question how such experiments were ever allowed to happen.

The Disturbing Fernald School Experiments

During the post-World War II era, one of America's darkest scientific experiments unfolded at the Fernald School in Massachusetts, where researchers from Harvard and MIT fed radioactive oatmeal to developmentally disabled boys.

You might wonder how this could happen. Between 1946 and 1953, scientists studied calcium and iron absorption by serving contaminated meals to institutionalized children. The researchers enticed participation by creating a Science Club that rewarded boys with special privileges and treats.

The ethical implications were staggering – they didn't inform parents about the radioactive nature of the experiments, violating the Nuremberg Code's requirement for informed consent. The school had a troubling history even before these experiments, as it was originally named the Experimental School for Teaching and Training Idiotic Children.

In the historical context of the Cold War, this wasn't an isolated incident but part of a disturbing pattern of unethical research on vulnerable populations.

While the radiation exposure was relatively low, the moral breach was severe, leading to a $1.85 million settlement in 1998 and sweeping reforms in medical research ethics.

What Really Happened to the Boys

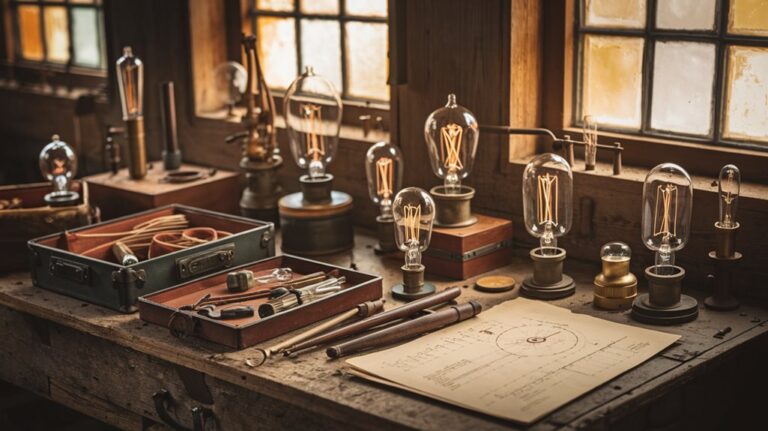

So what exactly transpired behind Fernald's walls? Without their knowledge or consent, 74 boys aged 10-17 were subjected to three different radioactive experiments. They were fed oatmeal containing radioactive iron tracers and milk with radioactive calcium. Some even received direct calcium injections.

The ethical implications were severe – these vulnerable children were fundamentally used as lab rats. These studies were overseen by state officials and universities from 1943 to 1973.

While a 1994 Massachusetts panel concluded there weren't significant health impacts, the long term effects remain concerning. The radiation exposure (170-330 millirems) gave each child a 1 in 2,000 chance of developing cancer.

Although the research helped advance osteoporosis studies, MIT later acknowledged their wrongdoing in exploiting these boys. The Senate ultimately condemned the practice of experimenting on vulnerable populations.

The Companies Behind the Tests

Several major institutions orchestrated these controversial experiments at the Fernald School.

You'll find Quaker Oats Company at the center of this shocking case, as they funded research to gain an edge over their competitor, Cream of Wheat. Their corporate ethics came under fire when it was revealed they'd partnered with prestigious institutions like MIT and Harvard to conduct these tests.

The experiments weren't just a commercial venture. Originally established as American Cereal Company in 1891, Quaker Oats had a long history of aggressive market competition. The company had used various unethical tactics, including feeding children radioactive calcium and iron without parental consent.

The Atomic Energy Commission and National Institutes of Health also backed the research, highlighting a broader pattern of unethical radiation testing during this era.

When confronted with historical accountability in 1997, Quaker Oats paid over $1 million to settle related lawsuits. MIT later admitted the boys received radiation equivalent to 30 chest x-rays, exposing the true scale of this ethical breach.

From Public Outrage to Legal Action

After journalist Eileen Welsome exposed the truth in her 1993 Albuquerque Tribune article, public outrage erupted over the government's role in feeding radioactive oatmeal to mentally-challenged children.

The story sparked intense media ethics debates and led Secretary of Energy Hazel O'Leary to declassify documents about human experimentation.

You'll be shocked to learn that a state task force investigation revealed MIT and Quaker Oats had violated basic informed consent principles at the Fernald School.

The children were deceived into thinking they were part of a special science club when participating in these experiments.

While they claimed the radioactive doses caused "no significant health effects," the damage was done.

The experiments occurred during a period when ethical standards were heavily influenced by Cold War security concerns.

The victims fought back through a $60 million federal lawsuit, ultimately securing a $1.85 million settlement from MIT and Quaker Oats.

The case pushed institutions to issue public apologies and established new precedents for protecting vulnerable populations in medical research.

A Dark Chapter in American Science

During America's Cold War era, one of science's darkest chapters unfolded at the Fernald State School, where researchers from prestigious institutions fed radioactive oatmeal to 74 mentally challenged boys.

You'd be shocked to learn that MIT and Harvard faculty conducted these experiments, backed by the Atomic Energy Commission, NIH, and even Quaker Oats.

The ethical implications were staggering. Parents weren't told about the radioactive materials their children would consume, and researchers deliberately targeted vulnerable populations who couldn't advocate for themselves. The boys were enticed to join the so-called "Science Club" with promises of special trips and gifts.

While experts later claimed the radiation exposure (equivalent to 30 chest x-rays) caused no significant health effects, the damage to scientific integrity was done. The facility remained in operation until 2014's final closure, marking the end of its century-long history.

These experiments exemplify how the pursuit of knowledge sometimes crossed moral boundaries, especially when researchers exploited those who couldn't protect their own interests.