Theater Riots Over Ticket Prices: The Day Britain Went Wild

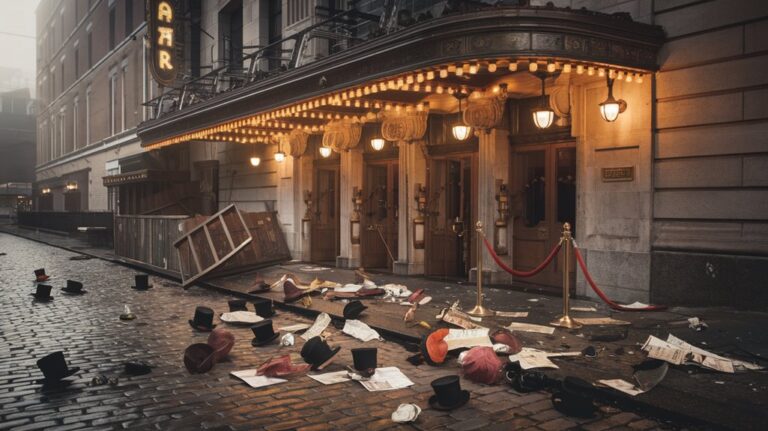

You might think of British theater as a refined affair, but in 1809, it erupted into chaos over something entirely relatable – ticket prices. When Covent Garden's management doubled admission costs after rebuilding from a fire, they didn't expect sixty-seven nights of creative rebellion. From releasing pigeons mid-performance to drowning out actors with noise-makers, ordinary citizens transformed London's premier theater into a battleground. What drove these well-mannered Georgians to such shocking acts of defiance?

The Spark That Ignited the Theater Revolution

When fire ravaged the original Covent Garden Theatre in 1808, destroying its costumes, scripts, and scenery, no one could have predicted the social uprising that would follow.

You'd think the public's £76,000 contribution to rebuilding efforts would've fostered goodwill, but management's decisions sparked outrage instead.

The new theater's increased construction costs led to higher ticket prices, but it wasn't just about money.

You're looking at a perfect storm of theatrical elitism: restricted gallery access for common folk, new private boxes for the wealthy, and price hikes during wartime economic hardship.

What began as a simple rebuilding project transformed into a symbol of class warfare, setting the stage for unprecedented audience empowerment.

The middle class wouldn't stand for it, and they were about to make their voices heard in what would become sixty-seven nights of continuous protests.

The insurers paid out only £50,000 for damages, leaving a significant funding gap for the reconstruction.

From Pigeons to Protests: Creative Chaos at Covent Garden

Though theatre management expected their audience to quietly accept the new pricing scheme, what they got instead was 64 days of creative chaos.

You'd have witnessed quite a spectacle if you'd been there in 1809. The Old Pricers (OPs) turned protest into performance art, staging mock fights and disrupting shows with singing and dancing.

They even carried a coffin into the theatre to dramatically oppose the changes. From the cramped "pigeon holes" of the gallery to the expensive private boxes below, protesters from all social classes united against the price hikes. The damage was so extensive that the theatre had to close for four nights of repairs.

Management even hired famous boxer Daniel Mendoza to control the crowds, but this only intensified the protests.

The OPs didn't just rely on noise – they got creative with their campaign, producing fake money and medals to make their point.

What made these protests remarkable wasn't violence or destruction, but rather their playful spirit and theatrical flair that ultimately forced management to cave in.

The Battle Between Management and the Middle Class

Behind the theatrical chaos of 1809 lay a deeper conflict between an ambitious management and an increasingly powerful middle class.

You'd find theater owners implementing management tactics that directly challenged long-standing traditions, particularly by eliminating half-price tickets after the third act.

What they didn't anticipate was the strength of middle class empowerment. These patrons weren't just passive consumers – they wielded significant economic influence and demanded more democratic theater practices. Similar to how pilot projects today test new approaches before full implementation, the theater owners tried experimenting with their pricing models.

When management tried to enforce their new pricing through professional boxers, it only fueled the resistance. The middle class responded with organized protests, creative disruptions, and sustained pressure that lasted three months. The opening night performance of Macbeth was drowned out by relentless boos and hissing from the angry crowd.

In the end, John Philip Kemble and his fellow managers had no choice but to bow to public demand and restore the old prices.

Economic Turmoil and Cultural Change in Georgian London

As London's population swelled to nearly a million by the late 18th century, you'd find a city transforming through intense economic and cultural upheaval.

The streets you'd walk were filled with both nobility and laborers, while industrial growth brought new wealth alongside urban poverty. You couldn't escape the grimy reality of overcrowded neighborhoods, where filth and horse manure created hazardous living conditions. Georgian theaters' prices were seen as a matter of public ownership by citizens across social classes.

Economic pressures forced women into various professions, while newcomers arrived daily seeking work as apprentices or servants. The lack of piped water supply made living conditions especially difficult for poor families.

While northern cities like Manchester and Leeds boomed with textile mills, London remained Britain's commercial heart.

Despite the squalor, cultural life thrived, especially in theaters that drew crowds from all social classes. These venues became more than entertainment spaces – they transformed into battlegrounds where class tensions played out nightly.

Legacy of the Old Price Movement in British Theater

When the Old Price Movement successfully pressured theater managers to restore affordable ticket prices in early 19th century London, you'd witness the birth of a transformative era in British theater history.

The uprising began when Covent Garden's management implemented restrictive pricing, sparking intense public resistance. This remarkable display of audience empowerment reshaped how theaters operated, leading to significant theater evolution throughout the 19th century. The 62-day campaign demonstrated the collective power of diverse social classes fighting for accessibility to the arts.

You'll find its impact extends far beyond just cheaper tickets – it fundamentally changed how managers engaged with their audiences and influenced cultural accessibility for generations.

- Theater managers became more responsive to audience demands

- The patent system was abolished in 1843, allowing more theaters to open

- Music halls emerged to serve diverse audiences

- Working-class people gained better access to theatrical entertainment

- Audience feedback became essential in shaping theater policies