Churchill Got a Doctor’s Note for Alcohol During Prohibition

You've probably heard about Winston Churchill's fondness for alcohol, but here's a fascinating twist: he actually got a doctor's prescription for it during Prohibition. After a near-fatal accident in New York City in 1931, Churchill found himself with both injuries and a clever solution to America's alcohol ban. The story behind this medical note isn't just about finding a legal loophole – it's a remarkable glimpse into how even the most powerful figures had to navigate the strict laws of the era.

The Near-Fatal Accident That Led to a Prescription

While crossing Fifth Avenue in New York City on December 13, 1931, Winston Churchill's life changed dramatically when he looked the wrong way and stepped into oncoming traffic.

Unemployed mechanic Mario Contasino's car struck the 57-year-old British statesman, leaving him with a fractured nose, two cracked ribs, and a deep head gash.

The accident aftermath saw Churchill rushed to Lenox Hill Hospital, where he identified himself as "a British Statesman" and requested pain relief. During this challenging time, he maintained his daily Champagne habit.

During his two-week hospital stay, he developed pleurisy while under Dr. Otto Pickhardt's care. Dr. Pickhardt notably prescribed alcoholic spirits for Churchill's recovery.

You'd be surprised to learn that Contasino, who was cleared of charges, visited Churchill in the hospital.

After his release, Churchill postponed his lecture tour, traveled to the Bahamas to recover, and later wrote about his experience in "My New York Misadventure."

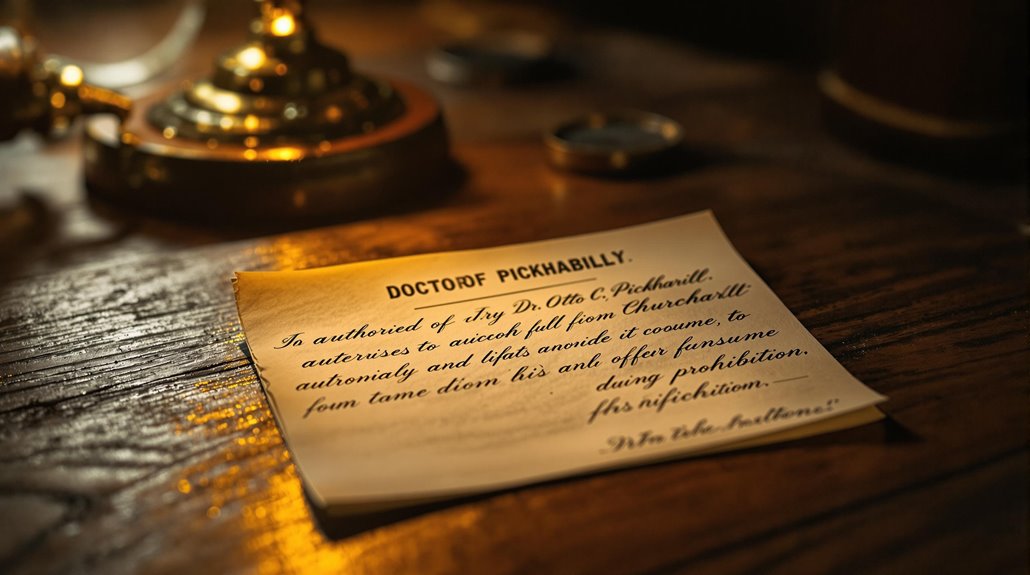

Inside Dr. Pickhardt's Notable Medical Note

During Churchill's recovery at Lenox Hill Hospital, Dr. Otto C. Pickhardt wrote what would become one of history's most famous alcohol prescriptions. The document, dated January 26, 1932, showcased both medical ethics of the time and the creative ways doctors helped patients navigate Prohibition's restrictions. Churchill needed this prescription after looking the wrong way and getting struck by a car while exiting a taxi in New York City. Pharmacies across America provided similar prescriptions to countless patients seeking alcohol during the dry years.

The prescription's key details reveal fascinating insights into this historical workaround:

- Specifically addressed to "Hon. Winston S. Churchill"

- Recommended "alcoholic spirits especially at meal times"

- Listed the quantity as "naturally indefinite"

- Required a minimum of 250 cubic centimeters

- Provided legal protection for Churchill's drinking habits

This notable medical note, now preserved in the Churchill Archives at Cambridge, exemplifies how physicians like Dr. Pickhardt used their professional discretion to prescribe alcohol during Prohibition while maintaining a façade of medical necessity.

Navigating Prohibition's Medical Loopholes

Despite Prohibition's strict ban on alcohol, America's medical system provided a surprisingly expansive network of legal loopholes that let citizens obtain liquor through their doctors.

You could visit a physician, pay $6 total for the diagnosis and alcohol, and walk away with a pint of liquor every 10 days – all perfectly legal under the Volstead Act.

Medical ethics quickly took a backseat as prescription abuse skyrocketed. Doctors prescribed alcohol for everything from cancer to anxiety, with whiskey being particularly popular. The American Medical Association even reversed its 1917 stance that alcohol had no scientific value, endorsing it for medicinal use. Religious leaders could still use wine for services under special permits.

Some physicians wrote hundreds of prescriptions daily, while pharmacies tripled in New York to meet demand.

Though the government tried controlling the situation through the Willis-Campbell Act, limiting doctors to 100 prescriptions per quarter, weak enforcement meant only a tiny fraction of physician permits were ever revoked.

Churchill's Relationship With Spirits

Throughout his life, Winston Churchill maintained an extraordinary relationship with alcohol that went far beyond casual consumption. His drinking culture became an integral part of his spirits legacy, demonstrating both his remarkable tolerance and strategic use of alcohol in leadership. He regularly began his day with a Scotch and soda while still in bed.

During the Boer War, he brought 36 bottles of wine and dozens of other spirits to the front lines.

You'll find Churchill's daily routine included:

- Starting his mornings with whiskey mouthwash

- Enjoying champagne during lunch and dinner

- Sipping brandy and Scotch throughout the day

- Consuming roughly two bottles of champagne daily

- Maintaining perfect composure despite high intake

While he despised drunkenness, Churchill believed alcohol enhanced his thinking and negotiating abilities.

He's famously quoted as saying he'd "taken more out of alcohol than it has taken out of me."

His carefully curated collection of preferred spirits, from Pol Roger champagne to Armenian brandy, reflected his sophisticated palate and unwavering commitment to quality libations.

A Historic Document's Lasting Significance

When Winston Churchill visited America in late 1931, a fortuitous car accident led to one of history's most notable medical prescriptions.

Dr. Pickhardt's note, now preserved in the Churchill Archives, reveals how prominent figures navigated the legal challenges of Prohibition-era America.

Churchill maintained daily alcohol consumption throughout his life which made the prescription particularly necessary.

The document's cultural implications extend far beyond Churchill's personal needs.

His need for the prescription arose after suffering severe head injuries while crossing 5th Avenue in New York City.

You'll find it referenced as a prime example of Prohibition's many loopholes, highlighting how medical prescriptions became a common workaround for obtaining alcohol.

With 11 million prescriptions written annually, Churchill's note wasn't unique – but it was certainly memorable.

The prescription stands as a fascinating intersection of 1930s politics, medicine, and law, demonstrating how even America's strict alcohol ban couldn't stop determined individuals from finding creative solutions within the system's framework.