Earth’s Two-Billion-Year-Old Nuclear Reactor: Fact, Not Fiction

You've probably heard that humans invented nuclear power in the 20th century, but nature beat us to it by about two billion years. Deep in the mines of Oklo, Gabon, scientists discovered something extraordinary: evidence of Earth's own nuclear reactor. This wasn't just a random concentration of radioactive materials—it was a fully functional nuclear fission reactor that operated for thousands of years. What's even more intriguing is how this natural phenomenon might change everything we think we understand about nuclear energy.

A Nuclear Discovery Deep in Africa

Shock rippled through the scientific community in 1972 when French scientists discovered something impossible at Gabon's Oklo uranium mine.

During routine uranium mining operations, they found that the concentration of uranium-235 was mysteriously lower than it should have been – 0.717% instead of the standard 0.72%.

Even more alarming, about 200 kg of uranium-235 had vanished from the geological formations.

What started as a frantic investigation into potential nuclear theft transformed into an extraordinary scientific revelation.

After weeks of intense study, researchers realized they hadn't uncovered a crime – they'd stumbled upon something far more remarkable.

The missing uranium hadn't been stolen; it had been "used up" two billion years ago in Earth's first and only known natural nuclear reactor.

This prehistoric power plant produced an impressive output of 100 kilowatts, enough energy to power roughly a thousand light bulbs.

The reactor's operation was made possible by the presence of groundwater as moderator, which helped control the nuclear reactions by slowing down neutrons.

Nature's Perfect Nuclear Storm

The formation of Earth's only known natural nuclear reactor required an extraordinary convergence of conditions that would be impossible to replicate today.

These natural phenomena occurred in Gabon when unique geological formations created the perfect environment for nuclear fission. Scientists have identified seventeen natural reactors at this remarkable site.

You'll be amazed at the precise conditions that aligned:

- A high concentration of uranium-235 (3.6%) that doesn't exist naturally today

- Porous sandstone filled with water that acted as a perfect moderator

- An oxygen-poor atmosphere that allowed uranium to concentrate

- Strategic placement of uranium ore deposits on granite layers

- Absence of neutron-absorbing materials that could halt the reaction

These conditions sustained nuclear fission for about a million years, producing 100 kilowatts of power through cycles regulated by groundwater seepage every three hours.

Similar to how gamma radiation bursts occur during thunderstorms, these natural nuclear reactions released significant energy through a precise combination of environmental factors.

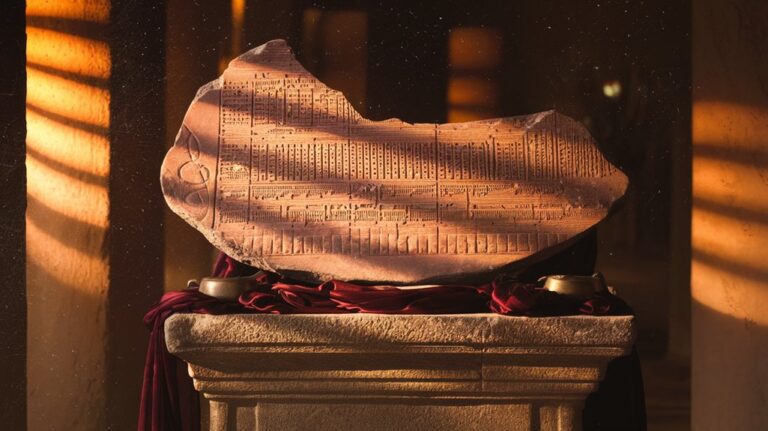

The Science Behind Earth's Natural Reactors

While modern nuclear reactors require complex engineering and safety systems, Earth's natural reactors operated through an elegant interplay of physics and geology.

You'll find the process relied on uranium enrichment that occurred naturally over millions of years, concentrating uranium-235 to levels above 3%.

The key to sustaining these reactions was neutron moderation by groundwater. When neutrons collided with uranium atoms, the resulting fission created heat that boiled the water.

As the water turned to steam, the reaction would stop until the water recondensed, creating a natural cooling cycle that prevented meltdown. The discovery was made when mass spectrometry analysis revealed unusual uranium ratios in ore samples.

This self-regulating process continued for roughly 150,000 years, with the reactors cycling every three hours and producing about 20 kW of thermal power – all without human intervention.

Scientists have discovered evidence of seventeen natural sites where these ancient nuclear reactions occurred in the Oklo region.

Unraveling Oklo's Nuclear Past

Deep within a uranium mine in Gabon, West Africa, French scientists made an extraordinary discovery in 1972 that would reshape our understanding of nuclear physics.

When analyzing ore samples, they found unexpected uranium depletion that mirrored the composition of spent nuclear fuel. This revelation led to an astounding conclusion: Earth had created its own natural fission reactors nearly two billion years ago.

The investigation revealed:

- At least 16 distinct reactor zones operated at Oklo

- Reactions cycled every 30 minutes with 2.5-hour cooling periods

- The reactors generated 100 kW of thermal power

- They produced 15,000 megawatt-years of energy

- A natural safety mechanism prevented meltdowns

You might wonder how it's understood.

The proof lies in the isotope ratios, which match those found in modern nuclear facilities, confirming this remarkable phenomenon. Ancient algae concentrated the uranium through natural processes, acting as Earth's first nuclear engineers. The presence of increasing oxygen levels in Earth's atmosphere made it possible for uranium to dissolve and accumulate in groundwater.

Lessons From a Prehistoric Power Plant

What ancient lessons could a two-billion-year-old nuclear reactor teach modern science? The Oklo sites reveal that prehistoric technology wasn't just possible – it was remarkably efficient.

You'll find that this ancient energy system maintained perfect balance through natural processes, operating at 100 kW for roughly a million years without human oversight.

The most valuable lessons come from Oklo's waste management. You're looking at radioactive material that stayed safely contained for 1.7 billion years, proving that long-term storage solutions exist in nature.

Scientists first discovered the site when they detected unusual isotope ratios in uranium samples from Gabon in 1972.

100 kilowatts power output during operation demonstrates the considerable energy potential of natural nuclear processes. The discovery of 16 reactor zones at the initial site provided scientists with multiple areas to study these remarkable natural phenomena.

100 kilowatts power output during operation demonstrates the considerable energy potential of natural nuclear processes. The discovery of 16 reactor zones at the initial site provided scientists with multiple areas to study these remarkable natural phenomena.