Ida Noddack’s Rejected Fission Theory: The Explosion That Proved Her Right

Like a prophet shouting into the void, Ida Noddack dared to challenge the scientific establishment in 1934. You've probably never heard her name, yet she predicted one of the most significant discoveries in nuclear physics. When she suggested that uranium atoms could split into smaller pieces, her colleagues dismissed her as an outsider who couldn't possibly understand atomic theory. But four years later, the explosion of scientific evidence would prove she'd been right all along. Now you'll discover why her story matters.

The Controversial 1934 Paper That Changed Everything

While many scientists dismissed her ideas at the time, Ida Noddack's 1934 paper in Angewandte Chemie marked a pivotal moment in nuclear physics.

In her groundbreaking publication, she challenged Fermi's chemical proofs and proposed something radical: uranium nuclei could split into large fragments when bombarded with neutrons.

Despite Noddack's influence on what would later be called nuclear fission, her hypothesis faced intense scientific skepticism.

She suggested that bombardment could create fragments that weren't necessarily neighboring elements – a concept that defied conventional wisdom.

Though she lacked experimental proof and a theoretical framework for energy conservation, her paper contained the first seeds of fission theory.

The scientific community's harsh rejection, particularly from Otto Hahn who deemed her work "ridiculous," wouldn't stand the test of time.

Her remarkable insight would be validated in 1938 when Otto Hahn and Strassmann finally confirmed nuclear fission through their experiments.

The discovery came only after Lise Meitner's careful calculations confirmed the energy release during the fission process.

Breaking the Nuclear Mold: Scientific Context of the 1930s

As nuclear physics underwent revolutionary changes in the early 1930s, scientists developed groundbreaking tools and theories that would shape Noddack's controversial ideas.

You'll find that scientific advancements were happening at breakneck speed, with Chadwick's discovery of the neutron and the first successful atom-splitting experiments by Cockcroft and Walton in 1932.

Nuclear experimentation flourished as researchers gained access to new tools like cyclotrons, cloud chambers, and Geiger-Müller counters.

Leading institutions like the Cavendish Laboratory and UC Berkeley's Radiation Laboratory pushed the boundaries of what was possible.

The Joliot-Curies' discovery of artificial radioactivity and Fermi's uranium experiments created an environment ripe for revolutionary theories.

Within this context of rapid discovery and technological innovation, you can understand why Noddack's radical ideas challenged the established scientific mindset.

In 1934, Noddack made a breakthrough by suggesting that heavy nuclei fragmentation could occur, though her peers largely dismissed this groundbreaking concept.

Mark Oliphant's achievement of the first artificial fusion reaction in 1932 further demonstrated the rapid pace of nuclear discoveries in this transformative era.

Why the Scientific Community Turned Its Back

Despite Ida Noddack's groundbreaking fission theory, the scientific community rejected her work for several compelling reasons.

Her status as a female scientist in the 1930s meant she faced significant gender discrimination, making it difficult to secure formal academic positions and gain respect from her male colleagues in physics.

The controversy surrounding her disputed discovery of element 43 (masurium) damaged her scientific integrity, causing many to view her subsequent work with skepticism.

After moving to the University of Strasbourg in 1942, her work became further isolated from mainstream scientific discourse.

You'll find that her lack of experimental evidence and theoretical framework to support her fission hypothesis further weakened her position.

The scientific consensus of the time, which firmly believed in Fermi's transuranic theory, created additional resistance.

Her revolutionary ideas would not be validated until Meitner and Frisch recognized atomic fission in early 1939, years after her initial proposal.

Without institutional backing and proper experimental validation, Noddack's revolutionary idea of atomic splitting remained on the sidelines of nuclear physics.

Vindication: The 1938 Discovery of Nuclear Fission

When Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann discovered nuclear fission in December 1938, they unknowingly validated Ida Noddack's earlier predictions.

You might find it fascinating how scientific communication at the time led to a rapid spread of this groundbreaking discovery.

Critics had previously dismissed her theories as far-fetched due to gender bias in the scientific community.

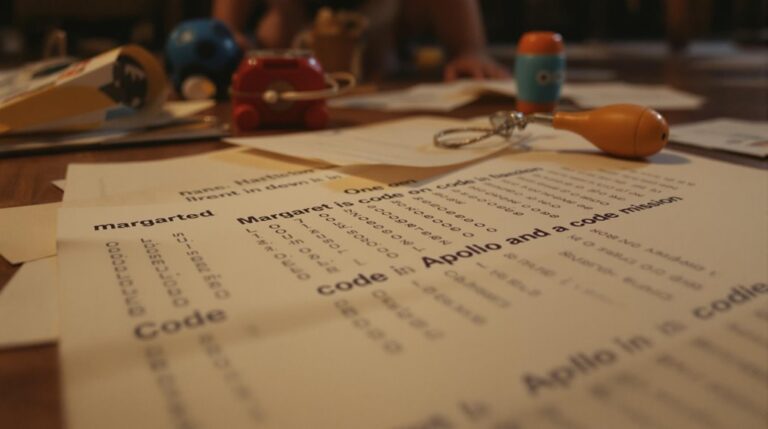

The historical recognition of Noddack's contribution came when she published a critical letter in March 1939, reminding the scientific community of her overlooked 1934 theory.

Kaiser Wilhelm Institute, Hahn and Strassmann conducted their groundbreaking experiments that would change nuclear physics forever.

Kaiser Wilhelm Institute, Hahn and Strassmann conducted their groundbreaking experiments that would change nuclear physics forever.

Consider these key developments that proved her right:

- Hahn and Strassmann's unexpected detection of barium from uranium

- Meitner and Frisch's theoretical confirmation of nuclear splitting

- Columbia University's first U.S. fission experiment

- Bohr and Wheeler's explanation using the liquid drop model

- Final verification of U-235 as the source of slow-neutron fission

This sequence of events ultimately vindicated Noddack's remarkable foresight from years earlier.

Beyond Recognition: Noddack's Impact on Modern Physics

The true measure of Ida Noddack's scientific legacy extends far beyond her vindication in nuclear fission. Her contributions to chemistry and physics continue to influence modern science in profound ways.

You'll find her impact in today's medical imaging technology, which relies on technetium – an element she predicted long before its official discovery.

Noddack's element discovery work, particularly her successful identification of rhenium with her husband Walter, demonstrated her exceptional skills in chemical analysis. Her insightful proposal that heavy nuclei split marked a revolutionary advancement in 1934. As the first female chemist in Germany's chemical industry, she broke significant barriers for women in science.

While she worked largely without pay or formal recognition, her insights into nuclear transmutation and element hunting laid vital groundwork for future research in transuranium elements and nuclear isomers.

Today's periodic table and our understanding of nuclear chemistry owe a significant debt to her pioneering work, even though she never received the Nobel Prize despite four nominations.