Chester Carlson’s Lonely Experiment: The Static Charge That Led to Xerox

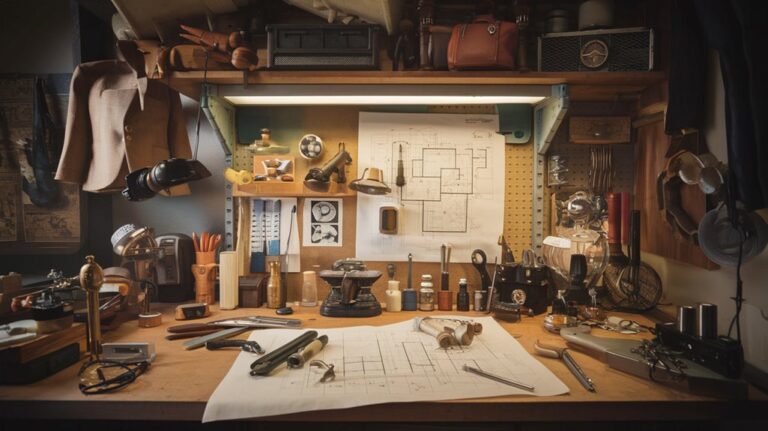

You've probably used a photocopier without giving much thought to its humble beginnings. In a small room above a bar in Queens, NY, Chester Carlson worked alone with basic materials like sulfur and a handkerchief to create something revolutionary. His 1938 experiment, combining static electricity with photoconductivity, wasn't just clever—it was the spark that would transform how we handle documents. Let's explore how this solitary inventor's persistence changed the modern office forever.

From Patent Clerk to Pioneer: The Early Years

Three major challenges shaped Chester Carlson's early life: poverty, family illness, and the Great Depression.

When you look at his childhood, you'll find a young boy who started working at age 12 to support his tuberculosis-stricken parents in San Bernardino. After losing his mother at 17 and later his father at 27, he persevered through adversity. Born into a family of Swedish immigrant parents, his early years were marked by constant struggle.

Despite earning a physics degree from Caltech, Carlson faced crushing job-hunting challenges during the Depression, sending out 82 applications before landing at Bell Labs.

His early inventions stemmed from a childhood fascination with printing, sparked by a toy typewriter and his amateur publication "This and That." His determination to create led him to document 400 inventions while working in Bell Labs' patent department.

Even as patent challenges led him from Bell Labs to Wall Street and then to P.R. Mallory Company, he never lost his passion for innovation.

The Static Electricity Breakthrough

While working late nights in his makeshift lab, Carlson discovered how to merge two scientific principles – photoconductivity and static electricity – to revolutionize document copying. Over twenty companies rejected him between 1939 and 1944.

His groundbreaking experiment used a zinc plate coated with sulfur as the photoconductive surface. After creating a static charge on the sulfur using a handkerchief, he placed a glass slide with India ink text on top.

When exposed to bright light, the illuminated areas lost their charge while dark regions retained it. You'd then see the invisible charged pattern spring to life as lycopodium powder clung to the charged areas, perfectly replicating the original text.

Despite showing promising results in partial tests, the development faced serious setbacks as the machine would malfunction after operations. To make the image permanent, he'd transfer the powder to wax paper and apply heat, fusing them together. This dry process marked the first time anyone had created positive copies without wet chemicals.

A Moment in Astoria: The First Xerographic Copy

On a crisp October morning in 1938, Chester Carlson and physicist Otto Kornei huddled in a modest second-floor room above an Astoria bar, about to make history.

With just $90 worth of basic equipment, they'd tackle experimental challenges that would change the world of document reproduction forever.

The Astoria significance became clear as they:

- Meticulously coated a zinc plate with sulfur and charged it using a cotton handkerchief

- Pressed a glass slide bearing "10.-22.-38 ASTORIA" against the surface

- Held their breath as lycopodium powder revealed the world's first xerographic image

You can imagine their excitement when, after heating the transferred image on wax paper, they'd created something permanent – a breakthrough that would revolutionize the modern office.

Their modest celebration lunch that day marked the beginning of what we now know as the photocopying industry. Years of copying law books at the New York Public Library while attending law school had inspired Carlson to find a better way. The idea had begun taking shape while he was working as a patent department employee at Bell Labs.

Twenty Years of Rejection and Persistence

The tide finally turned in 1944 when Battelle Memorial Institute, led by Russell Dayton, recognized xerography's potential and acquired Carlson's patents.

This partnership paved the way for collaboration with the Haloid Company, which would later become Xerox.

Under Joseph Wilson's leadership, Haloid committed to developing the technology, though it would take another decade of refinement before the first commercial copier reached the market in 1959—21 years after Carlson's initial breakthrough. Despite numerous rejections from companies like IBM, Carlson's persistence and resilience ultimately led to success in revolutionizing document reproduction. After several challenging years, Haloid introduced the Model A copier in 1949, which required over a dozen operations to produce a single copy.

The Birth of Xerox and a Copying Revolution

You can appreciate the commercial impact through these milestone achievements:

- The introduction of the groundbreaking XeroX Model A Copier in 1949

- The company's transformation from Haloid to Xerox Corporation

- The launch of the revolutionary Xerox 914 in 1959, which made automatic plain-paper copying accessible to offices worldwide

The pioneering process of electrophotography and xerography was developed through countless experiments with static electricity and photoconductivity.

This partnership catapulted both Carlson and Xerox to unprecedented success.

Driven by his early experiences with abject poverty, Carlson was determined to create an invention that would change lives and secure his financial future.

The invention transformed into a multibillion-dollar industry, revolutionizing how you handle documents while making Carlson a multimillionaire through his patents and company stock.