Mary Walton’S Streetcar Noise Silencer: Why Residents Thanked Her With Homemade Pies

You've probably never thought much about how noise pollution shaped the lives of 19th-century New Yorkers. Yet for residents living near the elevated railways, the thunderous racket of passing trains turned simple activities like conversations and sleep into daily struggles. That's where Mary Walton stepped in, armed with an unlikely combination of sand and cotton. Her ingenious solution didn't just quiet the trains—it earned her the sweetest form of gratitude her neighbors could offer.

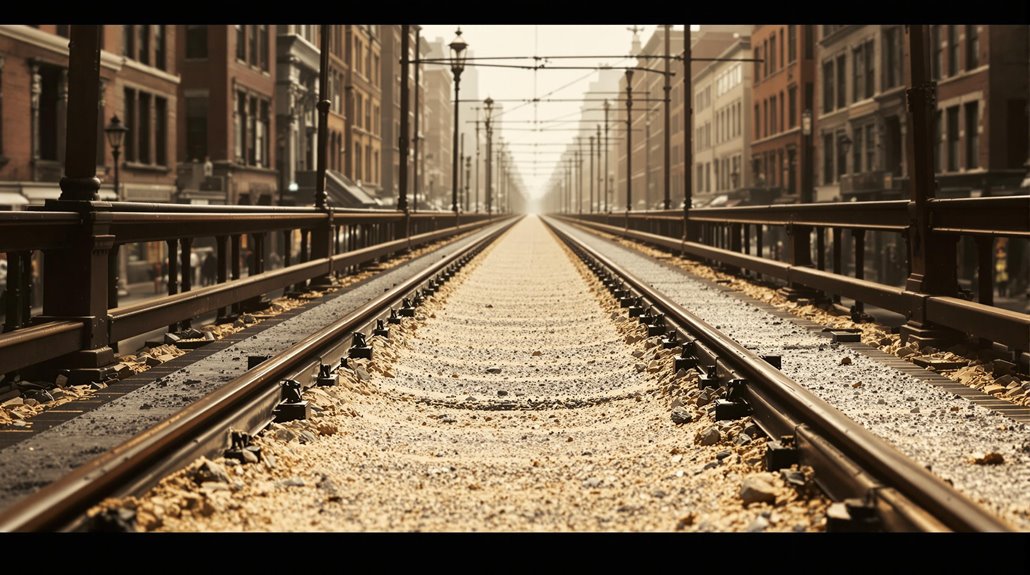

The Deafening Problem of New York's Elevated Railways

While New York's elevated railways revolutionized urban transportation in the late 1800s, they introduced an unprecedented noise crisis that plagued the city for decades.

You couldn't escape the thunderous roar of trains overhead, as iron structures amplified and echoed the sound throughout neighborhoods. This urban planning nightmare transformed vibrant streets into shadowy corridors where iron girders blocked natural light and dominated the skyline.

The lack of noise mitigation meant you'd struggle with daily activities – from holding conversations to getting a good night's sleep. By the 1930s, these once-celebrated engineering marvels had become symbols of obsolescence that desperately needed replacement.

If you lived or worked near the tracks, you'd face plummeting property values and constant disruptions.

Studies revealed the noise wasn't just an annoyance – it considerably impacted children's education, with teachers losing over 11% of classroom time daily to the deafening din.

From Boarding House Owner to Brilliant Inventor

Unlike many inventors of her era, Mary Walton's journey to innovation began with her boarding house near New York's Gilbert Elevated Railway.

Thanks to a father who believed in educating his daughters, she developed an innovative spirit that would later revolutionize city life. Her early writings were published in the Weekly Transcript of Lexington, Kentucky.

When smoke and noise from passing trains threatened her boarding house business, Walton didn't just complain – she acted.

While Thomas Edison gave up after six weeks of trying to solve the pollution problem, she persisted. She spent days riding trains, studying their mechanics, and even built a model railroad track in her basement.

Her determination led to two groundbreaking patents: one for reducing smokestack emissions and another for dampening railway noise. Her sound-dampening system was so successful that she was able to sell the rights to the Metropolitan Railroad for $10,000.

Testing Solutions in a Basement Laboratory

Before taking her invention to the streets, Mary Walton transformed her basement into an impressive acoustic laboratory complete with miniature streetcar tracks and specialized testing equipment.

You'd find her meticulously testing different combinations of sand and cotton while measuring noise levels with the era's primitive sound devices.

Her dedication to acoustic innovation showed in every detail of her makeshift facility. She'd installed sound-dampening walls for ideal sound isolation, allowing her to capture accurate measurements as she ran her scale models along the tracks. Like modern test methods, she ensured her facility had minimal flanking transmission for accurate results.

Through countless iterations, she refined her silencer design, carefully documenting each test result. Much like today's acoustic metamaterials that achieve 94% noise reduction, she adjusted the materials and ratios until she achieved optimal noise reduction, preparing for the eventual leap to full-scale testing.

The Simple Power of Sand and Cotton

The genius of Mary Walton's noise silencer lay in its elegant simplicity: sand and cotton, two common materials that proved remarkably effective at taming streetcar noise.

You'll find that sand's high density provided the perfect mass barrier, blocking noise transmission by filling gaps and voids where sound could escape.

Meanwhile, cotton's natural material properties made it an excellent sound absorption companion – its fibers trapped sound waves and converted them into heat, particularly effective for those higher-frequency rattles and squeals that plagued city residents.

Similar to modern mass loaded vinyl solutions, Walton's innovative design demonstrated how dense materials could effectively block unwanted noise transmission. Her approach mirrored today's dampening materials that reduce vibrations in various applications.

What made Walton's solution brilliant was how she combined these everyday materials to create a dual-layer defense against noise.

Sand delivered the heavy blocking power, while cotton's porous nature absorbed the remaining sound vibrations, giving city dwellers the peace they desperately sought.

A Woman's Solution to a City's Nightmare

Living near New York City's elevated railway tracks in the 1880s meant enduring what residents called an "infernal din" – a relentless assault of screeching metal, thundering wheels, and vibrating steel that made everyday life unbearable.

Enter Mary Walton, a pioneering female inventor who wouldn't accept noise pollution as an inevitable part of urban life. While city officials struggled to address the crisis that was driving down property values and disrupting sleep, Walton took matters into her own hands. Much like how Erna Schneider Hoover would later revolutionize telephone systems, Walton saw a pressing infrastructure problem that needed solving.

You'd have found her in her basement, meticulously testing different combinations of materials until she discovered the perfect solution: a wooden box filled with sand and tar-soaked cotton batting that absorbed the railways' violent vibrations. In 1881, the Metropolitan Railroad purchased her groundbreaking noise reduction system.

Her urban innovation proved so effective that the Metropolitan Railroad quickly implemented it, bringing blessed relief to countless grateful residents.

Sweet Success: How Grateful Neighbors Showed Their Thanks

Sweet aromas of freshly baked pies wafted through neighborhood streets as grateful residents expressed their thanks to Mary Walton.

You'd find neighbors carrying homemade desserts to her doorstep, each pie representing their heartfelt appreciation for the peace she'd brought to their lives.

This spontaneous display of community gratitude went far beyond simple desserts.

You'll see how Walton's inventive solutions greatly improved the neighborhood's quality of life. Families could finally sleep soundly, property values increased, and stress levels dropped significantly.