Did a Nuclear Manhole Cover Beat Sputnik Into Space?

In 1957, a single high-speed camera captured just one frame of a 2,000-pound steel manhole cover as it vanished into the sky at an estimated 125,000 mph—nearly six times faster than escape velocity. You've probably heard of Sputnik's historic journey as humanity's first artificial satellite, but there's a chance that an accidental piece of nuclear test debris beat it to space by several months. The truth behind this peculiar piece of Cold War history lies in the details of Operation Plumbbob's Pascal-B test.

The Nuclear Manhole Cover Experiment: What Really Happened?

While most space-faring objects undergo careful planning and engineering, one of humanity's fastest launches into space may have been completely accidental.

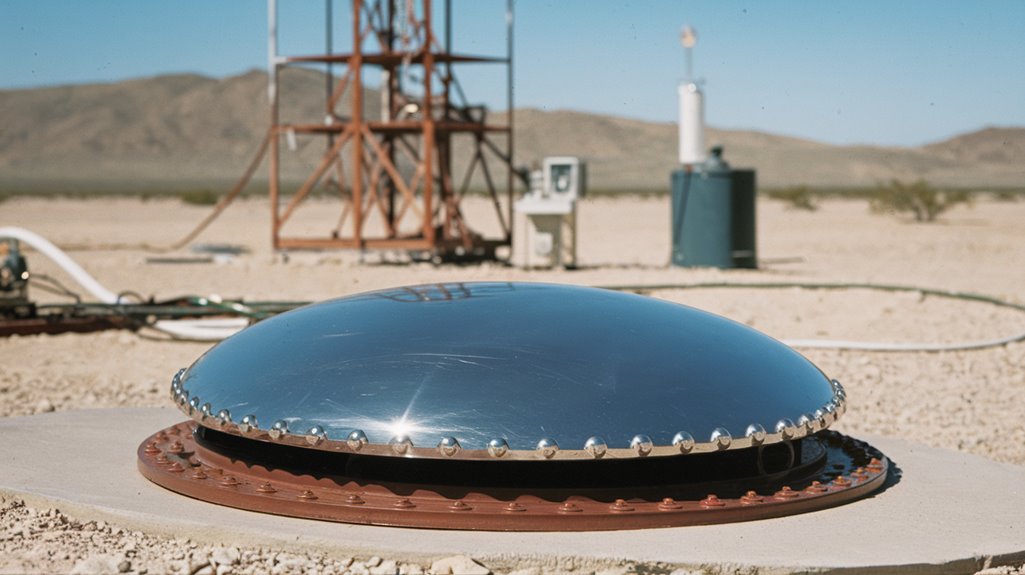

In 1957, during Operation Plumbbob's nuclear physics experiments, scientists at the Nevada Test Site conducted two peculiar tests: Pascal-A and Pascal-B. You might be surprised to learn they placed nuclear devices at the bottom of deep vertical shafts, covered by a 2,000-pound iron lid. These tests were designed to contain nuclear fallout in underground chambers.

When the bombs detonated, the Pascal-B test transformed into an unexpected space exploration milestone. The massive explosion launched the manhole cover at an estimated 125,000 miles per hour—five times Earth's escape velocity. The explosion created a flash that was brighter than 1 million suns.

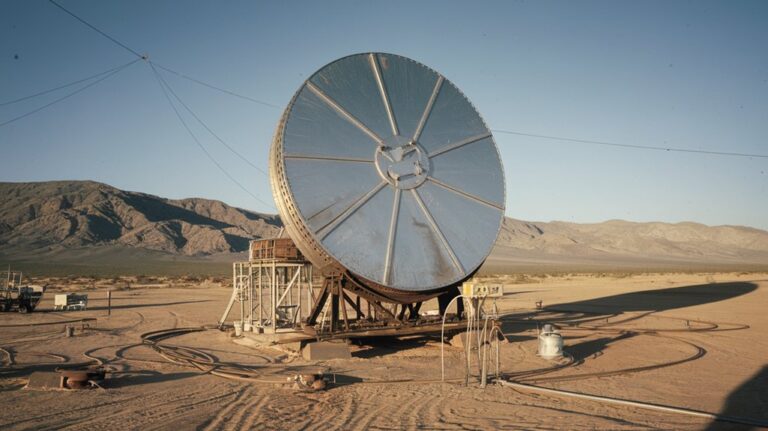

A high-speed camera caught just one frame of the lid's journey, and it was never seen again, potentially becoming the first human-made object to reach space, months before Sputnik.

Breaking Down the Speed and Physics

Since the Pascal-B test's infamous manhole cover launch defied expectations, let's examine the mind-boggling physics behind its estimated 125,000 mph journey. The nuclear blast created pressure that instantly vaporized concrete and generated light over 1 million times brighter than the sun.

You'll find the speed calculations astounding – at over 37 miles per second, this cast-iron disc outpaced even modern spacecraft like New Horizons. The 218-pound W-25 warhead used in these tests demonstrated the incredible destructive power of even relatively small nuclear devices. Los Alamos Laboratory conducted these groundbreaking tests that pushed the boundaries of nuclear physics.

The manhole physics involved complex factors, with speed estimation complicated by atmospheric friction and heat transfer coefficients. While Dr. Brownlee calculated the velocity at five times Earth's escape velocity, most physicists believe the intense heat would've vaporized the cover like a reverse meteor.

Despite ongoing debate, one fact remains clear: the high-speed camera captured just a single frame before the cover vanished into history.

The Race to Space: Manhole vs. Sputnik

The timing of the Pascal-B test created an intriguing historical overlap with humanity's first steps into space. Just weeks before Sputnik 1's historic launch, nuclear testing at Operation Plumbbob had inadvertently produced what might've been the fastest human-made object ever created. Operation Plumbbob experiments were originally designed to reduce radiation exposure from nuclear tests.

While you'd expect Sputnik to claim the title of first human-made object in space, the manhole cover from Pascal-B might've beaten it by mere weeks. Sputnik traveled at 8 km/s in its carefully planned orbit, but the nuclear-propelled cap reached an astonishing 60 km/s. The rocket's total liftoff thrust of 3.89 MN helped ensure Sputnik's controlled journey into orbit, unlike the chaotic manhole launch.

However, there's a significant difference: Sputnik successfully completed 1,440 orbits, while the manhole cover likely vaporized in the atmosphere. This quirky intersection of space exploration and nuclear testing demonstrates how two vastly different approaches to reaching space emerged during this pivotal period.

Scientific Evidence and Expert Analysis

Scientific analysis of the Pascal-B manhole cover's journey hinges on a single frame of high-speed camera footage and complex theoretical calculations.

The theoretical implications suggest the cover reached an astonishing 125,000 miles per hour – more than five times Earth's escape velocity and far exceeding NASA's New Horizons spacecraft speed.

Dr. Robert Brownlee's high speed physics analysis initially seemed improbable, but he later concluded the cover's mass and velocity might've enabled its survival through the atmosphere.

You'll find competing viewpoints among physicists, though, as some argue atmospheric friction would have caused the cover to burn up or fall back to Earth.

The cover's unaerodynamic shape adds another layer of uncertainty to its fate.

Despite extensive searching, you won't find definitive proof of where this accidental space pioneer ended up.

The Legacy of Operation Plumbbob's Fastest Object

While experts continue debating the manhole cover's ultimate fate, its incredible journey left an indelible mark on human spaceflight history.

You might be surprised to learn that this unintentional space launch during nuclear testing potentially made it the fastest human-made object for over 65 years, until the Parker Solar Probe finally exceeded its speed in 2023.

The historical impact of Operation Plumbbob's Pascal-B test extends beyond its original military purposes.

Consider that this one-ton iron lid may have reached space months before Sputnik, traveling at a mind-boggling 125,000 miles per hour – more than triple the speed of NASA's New Horizons spacecraft.

Dr. Robert Brownlee's calculations using high-speed camera data confirmed the extraordinary velocity of the cover.

The initial high-speed imaging captured this extraordinary event, though much of the specific details remain debated to this day.

Whether or not the cover survived its journey intact, it represents an extraordinary, albeit accidental, milestone in humanity's reach for the stars.