Hertha Ayrton’s Electric Arc Lamp: The Gendered Battle for a Lab and a Patent

Like a spark that refuses to die, Hertha Ayrton's battle for scientific recognition illuminated the dark corners of Victorian gender bias. You'll find her story isn't just about perfecting the electric arc lamp—it's about a woman who dared to claim her space in a man's world. While her male contemporaries worked freely in their laboratories, she had to fight for every patent, every experiment, and every moment of validation. What she achieved would change not only the future of lighting but the landscape for women in science.

The Rise of a Mathematical Prodigy at Girton College

A mathematical brilliance emerged when Phoebe Sarah Marks, later known as Hertha Ayrton, entered Girton College, Cambridge in 1876.

Despite educational challenges and financial constraints, you'll find her story remarkable: she secured support from feminist communities to pursue her studies and excelled under physicist Richard Glazebrook's tutelage.

Her mathematical innovation surfaced early as she published problems and solutions while founding a mathematics club with Charlotte Scott.

Though illness affected her final exams, resulting in a third-class degree, she didn't let this deter her.

Growing up, she overcame significant hardship after her father's death in 1861 forced her mother to support the family through needlework.

She was encouraged by her family to think independently and pursue better educational opportunities than most men of her time.

Beyond academics, she led the College Choral Society, established the Fire Brigade, and created a dedicated study group for female students.

Her undergraduate years culminated in developing a line-divider, which became her first patent in 1884, launching a lifetime of inventions.

Breaking Ground: From Line-Dividers to Arc Lamps

Building on her mathematical foundation, Hertha Ayrton's inventive spirit first manifested in her line-divider patent of 1884. At just 21, this invention impact signaled her remarkable shift from mathematics to practical engineering.

While at Girton College, she showcased her versatility by developing a sphygmomanometer and founding the college's fire brigade.

Her entry into electrical engineering began through her husband's work with carbon arc lamps, the period's premier lighting technology. Her studies at Finsbury Technical College laid crucial groundwork for her later achievements.

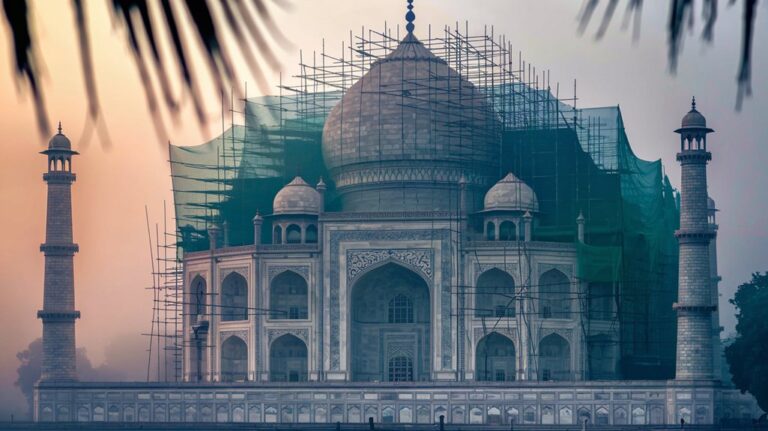

When you examine the engineering challenges she faced, you'll find they were formidable: hissing, flickering, and rapid oxidation of carbon electrodes plagued these early electric lights.

Ayrton tackled these issues head-on at Central Technical College, eventually discovering that oxygen interference caused the arc's instability. Her solution of excluding oxygen revolutionized arc lamp technology. She presented her groundbreaking findings as the first woman to lecture at The Institution of Electrical Engineers in 1899.

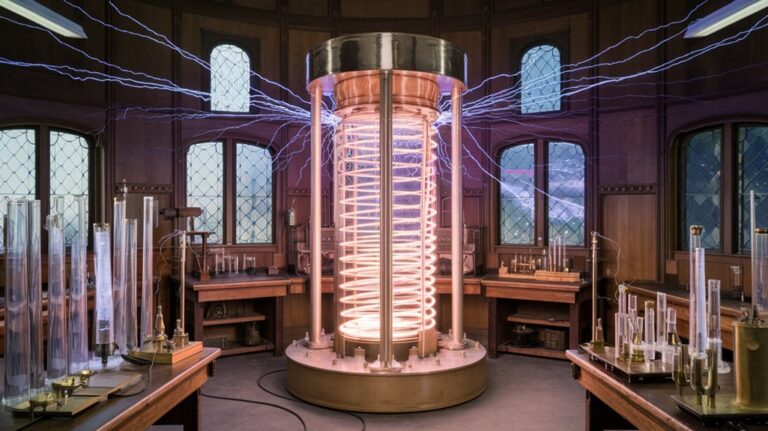

The Science Behind the Hissing Arc Mystery

While many inventors of the era struggled to understand arc lamp behavior, Hertha Ayrton's methodical investigation revealed the complex physics behind the mysterious hissing phenomenon.

She discovered that the hissing wasn't a simple defect but rather a result of the arc's nonlinear characteristics and negative resistance properties.

You'll find that when oxygen interacts with the carbon rods, it creates an unstable environment that affects arc behavior.

The flickering occurs as air contacts the carbon crater, producing inconsistent light output.

What's particularly fascinating is how the varying voltage generates controllable sound frequencies – a phenomenon first documented by Dr. Simon in 1898.

Duddell later demonstrated how an LC resonant circuit could be added to control these frequencies more precisely.

Ayrton's groundbreaking research at the Central Technical College in Kensington helped explain these complex interactions, leading to significant improvements in arc lamp technology and street lighting applications. The lamp's ability to produce daylight-like illumination made it especially valuable for early street lighting systems.

Defying Victorian Era: A Woman's Fight for Patent Rights

Despite the restrictive Victorian era laws that prevented women from owning property until 1882, Hertha Ayrton fought relentlessly to secure her intellectual rights as an inventor.

When she filed her first patent in 1884 for a mathematical line-divider, she needed financial backing from suffragists Lady Goldsmid and Barbara Bodichon to cover the costs.

Born into humble circumstances, she pursued her education at Finsbury Technical College where she developed her expertise in electricity. Her father's death in 1861 led her to become the family breadwinner early in life.

Facing intense gender discrimination, she'd go on to secure 26 patents throughout her career, including 13 for arc lamps and electrodes.

She overcame these barriers through strategic collaborations with male colleagues, including her husband William, while leveraging press coverage and her suffragist connections.

Her persistence led to groundbreaking achievements, becoming the first woman to present at the Institution of Electrical Engineers and its first female member.

Legacy of Light: How Ayrton Changed Street Illumination

Three major breakthroughs in Ayrton's arc lamp research revolutionized street lighting across Victorian England. She discovered how oxygen interacted with carbon rods, established the mathematical relationship between arc components, and developed longer-lasting materials that transformed urban illumination.

You'll find her influence most evident in the enhanced public safety of 19th-century cities. Her solutions to the notorious hissing and flickering problems meant streets stayed consistently lit, while her improved carbon rod design markedly reduced maintenance costs for municipalities. Despite early resistance, she effectively identified that carbon rods hissing was caused by oxygen interactions in 1893. Being the first woman at IEE to present her findings in 1899, she faced significant skepticism from her male colleagues.